The Lady Novelist and the Movie Moguls.

Jane Austen film adaptations, whether they take the form of miniseries, Bollywood musical extravaganzas, or hip Hollywood comedies, inspire vigorous and occasionally acrimonious debates among fans of the novels and movies alike. For example: Will the women of the English-speaking world ever accept any actor besides Colin Firth in the role of Mr. Darcy in Pride and Prejudice? Who makes a better Emma Woodhouse, Kate Beckinsale or Gwyneth Paltrow? And how could any woman turn away Alan Rickman (definitely out of Snape mode) in Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility? Discuss.

Well, we're not done with the Austen screenplays yet, given that a biopic, Becoming Jane, is strolling genteelly into theaters this weekend, and new adaptations of the novels are on their way to American television. Brew another pot of tea, gentle readers and viewers, and settle in for the long haul.

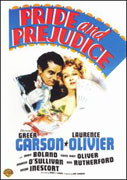

But even with all the current Austen projects, I want to reach further back, to the first half of the 20th century, when the movie studio system and the Hays Office held sway, and literary adaptations emerged on screen in forms we might not recognize today. Our destination: Robert Z. Leonard's 1940 film of Pride and Prejudice.

In the summer of 1989, not long after the death of Laurence Olivier, a friend and I rented the 1940 Pride and Prejudice. Having read, re-read, and loved the novel, I was at first taken aback by the alterations to the story. Characters and plot had been trimmed, and the more biting satire softened. Even the gowns were Victorian and not Regency garb.

In the summer of 1989, not long after the death of Laurence Olivier, a friend and I rented the 1940 Pride and Prejudice. Having read, re-read, and loved the novel, I was at first taken aback by the alterations to the story. Characters and plot had been trimmed, and the more biting satire softened. Even the gowns were Victorian and not Regency garb.I soon came to realize, however, that the film was a reflection of its times, with a screenplay adapted -- by Jane Murfin and Aldous Huxley, no less -- from what had been a successful stage production. Some of Jane Austen's humor and social commentary, such as the identification of the Bennets' silly cousin Mr. Collins as a clergyman, did not survive the attentions of the Hays Office. Oh, how times have changed!

In spite of all, I took a liking to the movie, watching it repeatedly over the years, particularly in times of sorrow and exhaustion. The actors, the screenplay, the very score became my friends, alongside Jane Austen's novels and some of their other film adaptations.

A young Laurence Olivier is convincingly rigid as the proud, wealthy Fitzwilliam Darcy, whose disastrous first encounter with Elizabeth Bennet (Greer Garson) sets off a battle of wills. But if Olivier is at first convincingly disdainful, he then gradually unveils a touching vulnerability -- and ardor. By the time his on-screen exchanges with Garson take a serious turn, he's fairly smoldering across the pianoforte at her. You can almost hear the sighs of the women at those 1940s screenings.

Given her roles in films such as Random Harvest and Mrs. Miniver, Greer Garson seems an unusual choice for Lizzy Bennet, more chic Londoner than English rose. But she has the wit and intelligence for the part, and is a worthy sparring partner to Olivier. The role demands a strong, assertive woman, and Garson is more than up to the challenge.

Aside from watching the battle of the sexes unfold, much of the film's fun is in cataloging the line-up of familiar faces from the golden age of Hollywood:

Mary Boland, so memorable in The Women, is here cast as the ultimate desperate housewife: Mrs. Bennet, the mother of five daughters with no dowries and a decided shortage of prospective suitors.

Edmund Gwenn is enshrined forever in popular imagination for his role in Miracle on 34th Street but was also a memorable ensemble player in films such as Foreign Correspondent, Between Two Worlds, and The Trouble with Harry. His sly, snarky Mr. Bennet is one of the film's delights.

Frieda Inescort was a stage-trained actress who never quite got the treatment from the studios she deserved but nevertheless won roles in a number of classic films, appearing opposite Katharine Hepburn in Mary of Scotland and Bela Lugosi in Return of the Vampire. Inescort, using that divinely icy voice to perfection, has a triumph here as Caroline Bingley, snob, romantic rival, and obstacle to the Bennet sisters' happiness.

A heart-breakingly young Maureen O'Sullivan is cast as Garson's sensitive, lovelorn sister Jane.

Ann Rutherford (yes, from the Andy Hardy series) plays the cheeky youngest Bennet sister, Lydia, who sets in motion as much scandal as the Production Code will allow.

Marsha Hunt, a pretty and stylish actress in private life, is enlisted to don spectacles and sing off-key as the family bluestocking, Mary. The scene where Garson reacts to Hunt's butchering of "Flow Gently, Sweet Afton" is a classic.

Melville Cooper, an instantly recognizable character actor, steals the show as the obsequious Mr. Collins. That's all I'm going to tell you; just enjoy.

And best of all, Edna May Oliver, star of the Hildegarde Withers series, duly intimidates everyone as Olivier's terrifyingly snobbish aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh.

Herbert Stothart, a contract composer for MGM, provides the music, and if you don't recognize the name, you have undoubtedly been exposed to his arrangements and compositions in films a diverse as The Wizard of Oz, After the Thin Man, and A Night at the Opera.

Stothart uses musical themes extensively, employing familiar passages to establish character and setting. For example, the arrival of the dotty and nervous Mrs. Bennet is heralded by "The Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks" from Pictures at an Exhibition, and "Now Is the Month of Maying" reminds us that we are in an England village, and at the loveliest time of the year.

The DVD extras include the theatrical trailer, which makes a nice change from today's predictable fare: not an explosion in sight, and no Don LaFontaine narration (He was, after all, only a baby in 1940). For some reason the DVD also includes a cartoon about a bear and a short dealing with the U.S. Navy -- the better to recreate that 1940 movie-going experience, I suppose.

0 Comments:

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home