Enigmas and Epics

In Kenneth Branagh's Midwinter's Tale (AKA In the Bleak Midwinter), Michael Maloney, as an actor-director brought to the end of his tether during rehearsals for a holiday production of Hamlet, explodes before his horrified cast and wonders, rather profanely, why there's any point in going on living.

In Kenneth Branagh's Midwinter's Tale (AKA In the Bleak Midwinter), Michael Maloney, as an actor-director brought to the end of his tether during rehearsals for a holiday production of Hamlet, explodes before his horrified cast and wonders, rather profanely, why there's any point in going on living.At which one of his actors (Mark Hadfield) says matter-of-factly: "Rachmaninoff. That bit in Brief Encounter. And Brief Encounter, actually. That makes life worth living." Obviously a guy after my own heart.

Not that I am going to unilaterally declare director David Lean our reason for going on, though at times that seems as good a plan as any. But I will say his talents and career enriched this life of ours. I have the happiest memory of watching Hobson's Choice in a dorm room with two close friends, discerning moviegoers both. What a gem of a movie that was for all of us, even late at night via portable TV. By gum!

And I doubt anyone can watch Brief Encounter without being haunted by it ever after, especially on journeys by train. Celia Johnson's voice-over gives me the chills.

In addition, David Lean perhaps single-handedly informed my impressions of the late John Mills, who gave markedly different but equally effective performances as a guileless shoemaker in Hobson's Choice and a disabled villager in Ryan's Daughter.

Lean's directing credits are surprisingly few but immensely varied: a droll little period comedy, various literary adaptations, an utterly adult romantic drama. But of course the man is chiefly known for his epics. Bring on the trains, the camels, the elephants, the hordes of extras dressed for winter on the steppe or the monsoon season!

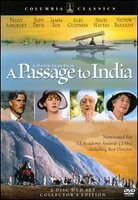

And as 2008 marks the 100th year since Lean's birth, several of his most acclaimed films are out in special two-disc editions, with wide-screen presentation and many extras: The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia, and A Passage to India.

Olsson's is stocking all three of them, in case you are contemplating an epic film fix. Whatever you opt to watch, it's going to be an intense, visually dazzling experience.

Aside from their visual power, the Lean films also assemble some of the finest casts ever seen in English-language cinema -- and capture great performances. For instance, whatever else Peter O'Toole does with the rest of his career, Lawrence of Arabia secured his place in movie history.

No prisoners!

Lean's swan song, A Passage to India, also boasts a phenomenal cast. Pride of place goes of course to the great Australian actress Judy Davis and to Peggy Ashcroft, playing two Britons who take a fateful journey into Asia. But the rest of the cast is equally memorable and includes such familiar faces as Saeed Jaffrey, Art Malik, and Roshan Seth, on the South Asian side, and James Fox, Nigel Havers, and Clive Swift, from the U.K.

Sharp-eyed PBS fans will recall that there was cross-pollination in Indian epics during the 1980s, as Malik and Ashcroft also played pivotal roles in the excellent TV adaptation of The Jewel in the Crown.

There was some overlap in the plots as well, for all that The Jewel in the Crown and A Passage to India were based on works by different authors (Paul Scott and E.M. Forster, respectively). Both concern themselves with painful aspects of Anglo-Indian relations at the waning of the British empire, as played out in the life of an educated young Indian man (Hari Kumar in Jewel, Dr. Aziz Ahmed in Passage).

As I watched A Passage to India once again, I was struck by how Lean keeps the tension between delight and discomfort. On the one hand, the movie is a sensory treasure, with India itself playing the starring role -- such wonderful plays of light and color, such amazing landscapes (and even a little bit of wildlife).

Before, however, you get too comfortable in your armchair travel, the story takes a heart-wrenching turn as a young Muslim physician (Victor Banerjee) attempts friendship with Britons Ashcroft, Davis, and Fox, with near-disastrous results. As the struggles unfold, the camera often zeros in on the faces of these actors -- enigmatic, stolid, ghostly, or wretchedly human -- and the expressions hint at what the script need not.

I don't care to reveal too much of the plot but will only say that it remains both thought-provoking and controversial, and manages to address the fragile, often tense, often ephemeral nature of human contact. "God has put us on Earth to love and help our fellow men," observes the practical yet culturally sensitive Mrs. Moore (Ashcroft). Later on, however, she notes: "Century after century of carnal embracement, and we're still no nearer understanding one another."

Once you have recovered from the emotional impact of the film, you might want to run through it all again with commentary (from producer Richard Goodwin) or gain an appreciation for the creative process, as depicted on the various featurettes included on the second disc. Alas, Ashcroft, Lean, and actor Alec Guinness (Godbole) are no longer with us, but quite a few of the cast and production team were available to share their perspective and Lean's legacy.

As Godbole observes in the film, "We are all part of a pattern we cannot perceive."

0 Comments:

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home